The story of visual kei

The glories, the tragedies and how these glammed-up rockers have kept their fans coming back for more

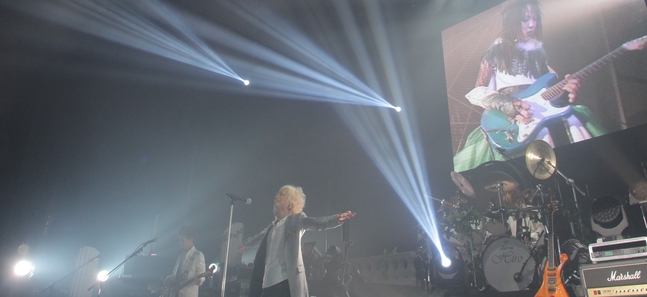

Despite a 10-year hiatus, X Japan is still rocking

Posted: Tue May 12 2015

Picture the scene: the bass player is dressed in a silver crop top and hot pants paired with thigh-high, heeled boots. The drummer’s waist-length, rainbow-coloured hair flails around an outfit of leather bondage gear with every thumping beat. The guitarist plays a wild shredding solo in a Marie Antoinette-style ball gown complete with wig and feathers. The singer winks a fake eyelashed eye from behind wisps of striking white hair before launching into death shrieks and erotic moans.

It would be easy to presume at least one of these band members we’re describing is a woman, or that they’re playing at a Halloween hair metal concert in 1987 – or even that this is some kind of performance art show. In fact, this is a fairly typical gig in the modern Japanese world of visual rock, with ‘visual’ being the operative word. Every weekend, at venues across Shinjuku, Shibuya and Ikebukuro, bands like this entertain a giddy crowd of almost entirely female fans who express their adoration through furious, synchronised arm movements and co-ordinated hair thrashing. This, oh wide eyed reader, is the intriguing world of visual kei.

Tangled roots

X Japan

X JapanVisual kei (meaning ‘visual style’, with the ‘kei’ pronounced ‘k’) is a musical genre – and beyond that a subculture – which grew out of a tangled mix of glam rock, punk and new wave influences, combined with kabuki theatre and shojo (manga for young women).

Heavy metal band X Japan, formed in 1982, are widely considered the pioneers of the genre and are also credited with originating the name, which was presumably adopted from their slogan, ‘Psychedelic violence crime of visual shock’. Notorious for their gravity-defying hairstyles, flamboyant clothes and outrageous make-up – which could be interpreted as both warrior-like and hyper-feminine – they predictably shocked parents whilst enthralling teenagers across the nation. Along with bands such as Buck-Tick and D’erlanger, X Japan introduced the country to shocking new visuals and sounds. They kickstarted a movement that saw musicians exploring the boundaries of excess, explicitness and androgyny while providing a unique take on Western music styles.

Although the music is generally described as heavy rock or metal (including everything from punk to power metal, and later nu-metal, hip-hop, electro and pop), visual kei actually spans a vast array of genres and continues to evolve. A better defining factor is, perhaps, the aesthetics. Dark, gothic, historical and traditional influences are common, and large elements of the look are comparable to the Western rocker styles of yesteryear: big hair, matching leather outfits and elaborate stage costumes.

While LA glam metal or the New York Dolls might have experimented with lipstick and lace, visual kei goes one step further in blurring the genders through cross-dressing and androgyny. It’s a theme that works for many of the bands’ story concepts, and also supports the Japanese appetite for idols and appreciation of male beauty and youth. These musicians aren’t just ‘guys in a band’, they’re a real-life representation of the unattainable princes in a girl’s comic book, combined with something cool and exciting. Maybe an ageless bisexual vampire or a fantastical erotic space pirate or a dazzling rock angel… you get the idea.

The volatile ’90s

Dir En Grey

Dir En GreyIt was in the mid-’90s that the visual scene really took off, with the likes of cross-dressing Shazna (partly inspired by Boy George) and classically influenced Francophiles Malice Mizer, who along with La’cryma Christi and Fanatic Crisis earned themselves the combined nickname ‘The four heavenly kings’. The scene started to become known for its passionate fans who immersed themselves in the subculture, bringing gifts to concerts, cosplaying to look like the band members and establishing strict gig etiquette.

However, at the same time, groups such as Luna Sea and Glay were toning down their look in order to appeal to a more mainstream market, and X Japan members had begun concentrating on solo careers. X Japan officially disbanded in 1997, and a year later, lead guitarist Hide, 33, was found dead in an apparent suicide, devastating his many fans. More than 50,000 people attended his funeral and numerous copycat suicides were reported.

Further tragedies would occur with the early deaths of Raphael’s 19-year-old guitarist Kazuki, just as the band was rising to fame in 2000, and the 1999 death of Malice Mizer’s drummer Kami, 27, just a few months after the abrupt departure of singer Gackt.

Raphael's memorial concert for band member Kazuki (on the screen)

Raphael's memorial concert for band member Kazuki (on the screen)

Despite the loss of these stars and the constantly changing lineups and break-ups, there was still a regular stream of newcomers. Monthly visual kei magazines (many of which continue today) and TV shows helped to perpetuate the movement, whether underground or in the charts. As anime’s popularity grew overseas, so did visual kei’s, with groups like Dir En Grey, The Gazette and Versailles in particular garnering attention in Europe and X Japan shocked parents and enthralled teenagers the US. Their main appeal? The uniqueness of the music, which features unusual chord progressions and timing, and of course their exotic visual aesthetic, which mirrors that of anime characters.

New genres

Oshare kei band Sug

Oshare kei band SugThe scene continued to diversify throughout the 2000s with wider musical crossovers and a constant push for visual innovation. Subgenres were defined – and debated. For example, angura kei (‘angura’ stems from ‘underground’) was the name given to bands that used traditional Japanese themes or uniforms, such as kimonos. Meanwhile, eroguro kei (taken from a combination of ‘erotic’ and ‘grotesque’) was for groups like Cali≠gari and early Dir En Grey, who incorporated disturbing horror themes and shock tactics into their stage shows, artwork and music videos. Kurofuku kei, on the other hand, was for groups who favoured classic but edgy all-black clothing.

Many bands formed in the mid-2000s or later are described as neo visual kei, a label that perhaps marks the point at which the focus changed from the music to the marketability of the group. This period saw the introduction of oshare (‘fashionable’) kei, used to describe a new style of pop-influenced visual bands with lighter themes and more playful looks. Bands like An Cafe, LM.C and Sug introduced a friendlier side of visual kei and appealed to an increasingly mainstream audience. Sug frontman Takeru even launched his own fashion label, Million $ Orchestra, in 2010 – a clever move, since visual kei has always had a strong influence on Japanese street style as well as host club fashion.

Pop goes the visual

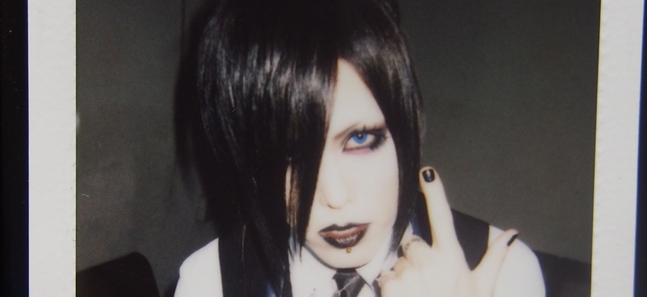

Up-and-coming band Kuroyuri to Kage's 'fan service' photo

Up-and-coming band Kuroyuri to Kage's 'fan service' photoThe visual kei movement today is basically a parallel of the J-pop idol system, which encourages a kind of pseudo intimacy between artists and fans – for example, by giving rewards to the most loyal fans, or rather to those who spend the most money. Bands are expected to take a hands-on approach to marketing, engaging in ‘fan service’ – which could be anything from uploading photos and videos on social media to acting out homoerotic role-plays on stage. For a movement that originally prided itself on being different, it now attracts those who want to ‘look’ visual kei. Genuine originality (in the music, at least) seems to be dying out. But the fans are still screaming, and that’s what counts. Isn’t it?

This article originally appeared in the spring 2015 issue of Time Out Tokyo magazine.

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment