Mount Fuji and the people of Edo

In part 5 of our ‘Transcreating Tokyo’ series, Takeo Funabiki takes on the sacred mountain

Posted: Thu May 01 2014

In Part 2 of this series, I wrote about Tokyo’s three levels of terrain, namely the plateau, the lowlands and the landfill, which are in turn encompassed by the sea and mountains. The sea here is of course Tokyo Bay, which I will write about next month, while the mountain refers not to the nearby peaks, but to the towering Mount Fuji.

Views of Fuji

Most people think that Mt Fuji is located in Yamanashi and Shizuoka prefectures, and it was indeed these two prefectures that filed the application for the mountain’s World Heritage registration, which it achieved last year. However, historically, Fuji attained the status it has today as the ‘mountain of Edo’. Tokyoites may have forgotten this fact simply because the mountain is usually hidden behind the tall buildings that have transformed the city’s skyline in recent decades.

Only 50 years ago, long after the end of the Edo period, Mount Fuji could be seen from anywhere in Tokyo. Born and raised in Setagaya, I saw the mountain clearly in both mornings and evenings when traversing the Odakyu line railway crossing. The depiction of a young migrant from the countryside renting a place at ‘Fuji View Apartments’ to start his Tokyo life was a staple of old-time TV dramas, and those in the know say that there are no fewer than 24 ‘Fujimi-zaka’ (‘Fuji View Hills’) in the city. Despite the geographical distance, the people of Edo felt a particular closeness to Mount Fuji.

In contrast, the gentle folk of Kyoto, inhabitants of Japan’s old capital and centre of culture, viewed Fuji as part of the rough and untamed eastern lands. Until the early Heian period (794-1195), the mountain was a highly active volcano, and the classic ‘Sarashina Diary’ described it as a place where ‘…smoke ascends, while fire blazes visibly at dusk’. This was written in 1020, when it seems that the volcano still occasionally spewed fire. The eruptions grew weaker, however, and when the Edo era began in the early 1600s, the mountain’s image had softened considerably.

Active volcanoes are distributed unevenly in the Japanese archipelago, with very few found in the western region from Kansai towards Chugoku and Shikoku. One can well imagine that this is why Japan’s early flourishing as a nation began in that area. It is also reasonable to assume that Tokugawa Ieyasu’s decision to build his capital city of Edo on the eastern Kanto plain had something to do with the fact that around 1600, Mount Fuji’s eruptions had lost most of their intensity. After all, Ieyasu was a native of Mikawa Province (the eastern part of modern-day Aichi Prefecture), and having extended his influence to places like Suruga (now in Shizuoka) in the Tokai region, he must have known Mount Fuji well.

The Fuji Cult

When seen from Edo, Mount Fuji has a gentle foot and a gorgeous snow-capped peak, but also carries the threat of a volcano – a major eruption again occurred in 1707, around 100 years after Edo was founded. This one mountain brings those two aspects together. In stark contrast to Kyoto’s mist-wrapped Higashiyama, Fuji’s dual existence is a perfect fit for the size and muscular personality of Edo/Tokyo, the giant man-made metropolis. In addition, Edoites’ feelings for Mount Fuji later surpassed simple fondness and assumed a religious character. Innumerable religious groups in Edo were named Fuji Koh, each of these dedicated to praying to and worshipping the mountain.

The Fuji cult had two aspects: one a relatively hidden theme of nature worship, in which mountains, waterfalls, rocks and other natural things were worshipped as kami (gods), and the other an intense aspect that produced believers who devoted themselves to asceticism in Mount Fuji’s caves, some even ‘withdrawing from the world’ and fasting themselves to death. Buddhist notions and the principle of yin and yang were mixed in, forming a doctrine so complex that it cannot be adequately explained here. Suffice to say that this religious movement was lively enough for the Shogunate to eventually crack down on it.

Fujizuka near Komagome Station

Built within the confines of the Fuji cult, the Fujizuka mounds, which remain scattered all over the city even today, are a very Edo-like and interesting part of the city’s history. Built from real Fuji lava, these ‘mountains’ range from a few metres to 10m in height and were constructed for the Fuji cult’s ritual purposes. Women, who were not permitted to climb the real Fuji, and weak-legged elderly people could scale these mounds as a substitute for the actual mountain. Interestingly, the Fujizuka thus express the down-to-earth and pragmatic aspect of Edo culture. The mounds existed in every corner of the city, and nearly 100 of them still stand today.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

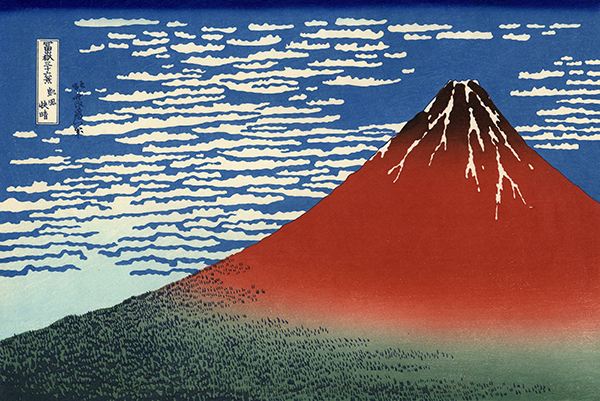

Fine Wind, Clear Morning

Inspiring artists – even in France

The ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai expressed Edoites’ love and awe of the sacred mountain in his Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. His most famous work, The Great Wave off Kanagawa, depicts Fuji in the background of the stormy sea. Hokusai also drew the mountain as seen from a variety of locations and in different situations, making his prints very popular. Most of them show Fuji as seen from Edo, but a few depict views from as far as Nagoya. Aside from the exceptional Fine Wind, Clear Morning that shows the mountain at sunrise, Mount Fuji is portrayed in small size in each of these prints. This demonstrates how the peak rises from a low, flat plain and can be seen clearly even from afar – one of the reasons why, despite the distance, the people of Edo made Mount Fuji their own.

Finally, it can be added that although the general ‘Japonism’ influence of ukiyo-e on Western painting is well known, it has also been theorised that Hokusai’s inclination to draw one mountain from many different angles, as he did in Thirty-Six Views, influenced Cézanne and provided the impetus for his Mont Sainte-Victoire series. The French, however, do not seem to hold this theory in very high regard.

Takeo Funabiki

Cultural anthropologist

1948, born in Tokyo

1972, BA, University of Tokyo, Faculty of Liberal Arts

1982, PhD in anthropology, Cambridge University, Graduate School of Social Anthropology

1983, University of Tokyo, College of Arts and Sciences, lecturer

1994, Professor

1996, University of Tokyo, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, professor

2012, retired from the Graduate School, Professor Emeritus

Field work conducted in Hawaii, Tahiti, Japan (Yamagata Shonaiheiya), East Asia (China, Korea) and Melanesia/Polynesia (Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea). Professional interests include 1) mechanism of mutual interference of human culture and nature, 2) the representations of ritual and theatre, and 3) changes in culture and society that occur during the course of modernisation.

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment