Posted: Tue Aug 27 2013

Taiyo Matsumoto has brought something special with him today. Sitting in the offices of his Japanese publishers in the Jimbocho neighbourhood, he reaches into his bag and – without so much as a flourish – extracts the final pages for the next volume of Sunny. Hand-drawn, delivered by hand: call him a traditionalist, but he still refuses to use computers in his work.

Matsumoto has always been a bit different. Inspired by European graphic novels as much as homegrown manga heavyweights such as Katushiro Otomo, he's spent the past quarter-century creating an utterly distinctive body of work. Cult classics including Tekkon Kinkreet and Ping Pong – both of which would later get the big-screen treatment – melded kinetic action with surrealism, dense wordplay and the odd bout of philosophising. (Not surprisingly, he's been translated more widely in French than English.) In his latest series, though, he's making things personal.

Sunny – which started in 2010 and is still ongoing – isn't an autobiography as such, but it draws heavily on Matsumoto's experiences of living in a foster home as a child. Told from the viewpoints of the home's various young residents, it's a quieter, more melancholy work than we've come to expect, although still ripe with humour and visual inventiveness. Unlike many of Matsumoto's other works, it's also made its way swiftly into English translation, courtesy of Michael Arias, the expat director who helmed the 2006 anime adaptation of Tekkon Kinkreet.

You were at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival earlier this summer. How was that?

It was a lot of fun. I thought they struck a good balance between manga and bandes dessinées [graphic novels]. You might wonder what I'd be doing at an event for what are basically kids' magazines, but I felt at home there.

Have you ever lived overseas?

Mmmm… I was interested in doing it when I was young, but nowadays I feel comfortable in Japan. The first time I went overseas was when I was 19, to do a story on kickboxing in Thailand. I was at university and had only just started drawing manga, but there was a kind of kickboxing magazine, and I drew a manga report for them. A couple of years after that, I went to France to do a story on the Paris-Dakar Rally, which ended up taking about three months. Japanese publishers still had a lot of money then. I wasn't really into cars or anything, so the series wasn't particularly interesting. [Laughs.] That was my first exposure to European comics, and it had a big effect on me – it still does. It was like looking into a different world.

Were there any artists in particular who really grabbed you?

There was Miguelanxo Prado, a Spanish writer, Enki Bilal and Moebius, who passed away last year – they all had a huge influence on me. I can't read French, so I was only looking at the pictures, but it was a style of drawing I hadn't seen before.

What are the main points of difference between European comics and Japanese manga?

It's hard to say for sure since I can't actually read them, but I felt like they didn't really have any rhythm. I thought there was a lot of text crammed into all the speech bubbles. It's changed a bit since then – there are writers who don't use much dialogue, or who choose to work in black and white instead. Around 25 years ago, all the bande déssinée writers were working in colour, and it was like they didn't waste a single panel. In Japanese manga, lots of panels are just for setting the scene, without any dialogue, but you don't see that very much in bandes déssinées. I've read some of it in translation, and you can't skip over anything, which I think can be a challenge for Japanese readers. You might say the balance is different.

Could you get bandes déssinées in Japan at the time?

I don't think they were available. You had to go abroad if you wanted to get them. Even now, I don't think most people know what ‘bandes dessinées’ are. You hear ‘amekome’ (American comics) much more often.

Were there any manga writers in Japan at the time who were influenced by European comics?

I'm not entirely sure, but Katushiro Otomo and Kamui Fujiwara were probably influenced – maybe Hisashi Eguchi too. I honestly haven't talked with them about bandes dessinées before, but I think that's true.

You've said before that Otomo was a big influence when you were young.

Yes, I've always felt I wanted to be like Otomo-san – I still do, in fact. [Laughs.]

What do you think was the biggest effect Otomo's work had on you?

The first time I came into contact with his work was when my mother gave me a copy of Domu when I was a high school student. I'd been reading manga since I was a kid – Osamu Tezuka, Shotaro Ishinomori – but Otomo's work was completely different. It looked cool, but there was more to it than that: it was like the pictures were moving, and the dialogue had a naturalistic feel to it. It wasn't the ‘manga world’: it was closer to the real world. I must have read it hundreds of times by now.

Do you think there are still a lot of artists now who just draw the ‘manga world’?

I think that everyone was in thrall to Otomo. People talk about the ‘Before Otomo’ and ‘After Otomo’ eras. There are all kinds of artists now, but I think you don't get so many people using the kinds of techniques I saw in the manga I read as a child.

Are you reading anything in particular at the moment?

I really haven't been reading much recently – only very occasionally. My wife [manga writer and illustrator Saho Tono] is quite an avid reader, so sometimes I'll pick up things that she's recommended to me. I'm the kind of person who keeps re-reading their favourite manga: even now, I go back to Osamu Tezuka's Black Jack or Kazuo Umezu's The Drifting Classroom every couple of years. Then of course there's Otomo. It's not a simple question of enjoying the manga. It's a slightly different feeling – like I'm in awe while I'm reading it.

What was the first manga you drew?

I joined the manga circle when I was at university, and the first thing I drew was about a gorilla who becomes a bike racer. That was probably the first manga I'd ever done.

There are noticeable variations in style between your major works, like Tekkon Kinkreet, Ping Pong, Takemitsu Zamurai and now Sunny. What's the thinking behind that?

With Takemitsu Zamurai, I deliberately changed my technique, but it's not normally something I'm conscious of. Often it's just a question of me seeing another artist's work and absorbing some influence from that: I might think, ‘This style would work well in manga form’, and give it a try. If you keep drawing in the same style it just gets boring. It's just a natural process of change.

Do you ever revisit your old work?

Er… not really. I get kind of embarrassed. [Laughs.] Just as an example, when I wrote Tekkon Kinkreet I was really confident in the language I was using, having fun with all the wordplay, but when I read it now, I feel like I was overdoing things. It's embarrassing, seeing what a know-it-all I used to be. On the other hand, when I wrote Ping Pong, my editors had asked me to do something sports-related, so it doesn't have a lot of my personal thoughts in there – meaning that it doesn't make me self-conscious when I re-read it now. It's just about sport – winning or losing – without all the philosophising. It's embarrassing when I get a glimpse of my 20-something self, always wanting to speak The Truth. [Laughs.] When I was in my 30s, I couldn't stand that, but since I got into my 40s I've started to see it as kind of cute.

There's that sequence in the second volume of Tekkon Kinkreet where Shiro ends up getting stabbed, and it pretty much took my breath away when I read it. Are you kind of seeing a film in your head when you draw it?

I think I was seeing it like an animation, yes. I was hardly sleeping when I wrote that – I was having to do it as a weekly serial, so I hardly remember doing any of it. The series wasn't very popular, either, so they wanted to wrap things up. I'd originally planned to do five volumes, but it ended up having to be three. Action sequences take up a lot of pages, so I was thinking about how many of those scenes I could actually include. After he gets stabbed, you see all these flowers and fish – those all take up space too, and since I knew I'd be finishing at volume three, I had to think hard about how much I'd be able to fit in. It wasn't about artistic concerns: it was about calculating pages.

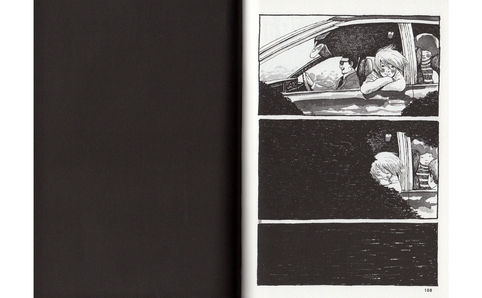

How about that bit in the second volume of Sunny, where you see Haruo looking out of a car as it disappears behind a bush?

Right, it feels like it's moving, like something in a film. I also drew that knowing that the book's designer, Shinichi Sekine, would be inserting a black page at the end of every chapter. I was thinking ahead to how it would look in book format.

© Taiyo Matsumoto/Shogakukan Ikki Comics

© Taiyo Matsumoto/Shogakukan Ikki Comics

Is there anything you drew then that you don't think you'd be able to do now?

With Ping-Pong, I think there's this energy to it that I couldn't re-create now. It's got a real power… There isn't a lot of action in Sunny. It's the first time I've written a manga like this, where there isn't much movement.

When did you first decide to write Sunny?

I'd wanted to do it ever since I made my debut. I had a lot of interesting experiences from living in a children's home when I was young, a lot of memories. But it would've been weird to start your career as a manga artist with a theme like that. [Laughs.] I also had some concerns about how the people I'd lived with then would respond if I wrote it.

Would it be overstating it to describe Sunny as autobiographical?

Right, it's not an autobiography. There are parts that are extremely close to my own experiences, but other bits were mostly made up. I actually wanted to make it more autobiographical at first, but I couldn't get it to work, so it settled into being about half real and half fiction.

Can I assume that the lead character of Sei is based most closely on yourself?

There isn't any one character who's supposed to be me. It's like I'm sharing my memories among all of the characters. People always say that I'm Sei, though. [Laughs.] I wasn't that well-behaved in real life.

Was this the first time you'd drawn on your own experiences?

It's the first time. When I was starting out, I wanted to write more from my own experiences, but when I tried to make manga based on things that had left a deep impression on me, I wasn't happy with the results, and it didn't go anywhere. When it's half invented, half based on real life, it's a lot easier. I think part of what makes manga good is that you're concocting an imaginary world. If you look at it that way, writing a manga entirely from your own experiences is cheating – but when you start thinking like that, you can't write anything. Whatever I write, there's always a slight sense of regret; with Sunny, I'm basing it on my experiences, and I'll think, ‘Well, anyone could do that.’ But it all comes out so easily, too. When I'm drawing something that actually happened, it's like the child on the page really exists. I'll draw a scene of a child crying, and I'm not sure if it's the child crying or if it's me. I haven't experienced that before.

How long did you live at the home depicted in Sunny?

It was for most of elementary school. I moved to live with a relative when I reached junior high, so it must have been around six years. I actually have a lot of stories from then that are much sillier or more fun, but the manga ended up being slightly melancholy.

There's a scene that really got me, where Sei tells the new arrival, Tooru, about how you gradually get used to the loneliness. Was that how it felt for you?

That's right. When I first went to the home, it felt like I'd die from the loneliness, but I gradually got accustomed to it. Over a month or two, I started laughing and going out to play with the other kids. When new kids came, they wouldn't stop crying for the first week, but then they'd stop. I was the same. I wasn't actually having fun, at the bottom of my heart, but it's like I slowly grew used to it.

What was it like when you left the home? Did it take a while to adjust?

I couldn't wait to get out, so I was really happy when I finally did. I wasn't sad: all I'd wanted for all that time was to be a normal kid, so I was overjoyed, really. I never went back after that, but I've had a few letters [from former residents] since starting the series.

You got Tekkon Kinkreet director Michael Arias to do the translation for the English edition. That Kansai dialect must've been tough.

Michael Arias: There's the Kansai dialect, the special onomatopoeias and ideophones, but actually the toughest thing was researching the cultural background: the pop culture of 1970s Japan. There's lots of stuff that doesn't come up in a Google search. They're not really important to the story, but there are all these little details scattered throughout the manga, and I wanted overseas readers to be able to understand them. Achieving that without just inserting foreign pop culture references instead was the biggest challenge.

Matsumoto: It was my wife who suggested getting Mike to do the translation. Mike's a movie guy, and he's got other work to do, so I didn't put the question to him for a long time. She kept saying, ‘So, have you asked him yet?’ [Laughs.]

Arias: I'm enjoying doing it. I wouldn't take on any old translation job – it's because it's this particular manga.

The Kansai dialect is another thing that's distinctive about Sunny, isn't it?

Matsumoto: Kansai dialect lightens the mood. No matter how heavy the subject is, it feels lighter. If you say ‘mou kanawan-wa…’ [‘it's hopeless’] it feels more light-hearted, whereas the regular version, ‘mou kanawanai na’, just feels tragic. I became conscious of that, using Kansai dialect in Sunny – it doesn't matter what you say, people feel inclined to laugh.

There haven't been many female characters in your previous works (which I think is because you said you weren't very good at drawing them), but there are quite a few in Sunny…

Yes, women didn't appear much in the work I did when I was younger. When my editor asked, ‘Why don't you include women?’ I'd say, ‘Why would I include women?’ [Laughs.] I didn't feel they were necessary at the time. This time, I was basing it on real life, and half of the kids at the home were girls, so I wanted to draw them too. For the female characters, my wife takes care of everything: drawings, direction, poses…

You've released three volumes so far, but how many do you have planned in total?

I'm thinking of having five of the characters on the cover: I've already done Haruo, Sei and Junsuke, and then it'll be Megumu and Kiiko, so that's five volumes in total. That's probably enough for this story, isn't it? [Laughs.] Then it'd be good to do Taro-chan for volume 6 and Sunny for the final volume. This could just go on and on… well, until people get sick of it.

The English edition of Sunny, Volume 1 is out now via Viz Media. Volume 2 will be released in November 2013

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment