Storytelling goes journalistic

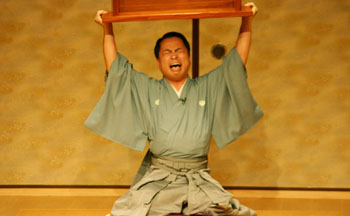

A traditional art form gets a passionate, contemporary touch

Posted: Thu Nov 04 2010

There are probably many people who, although they are interested in Japanese arts, have never experienced koudan storytelling. However, according to one professional storyteller, of all the traditional arts this is the easiest to understand and is a contemporary and interesting performing art. As many stories include heroes from Japanese history and fables, they tend to give the impression of being very formal. However, if you listen to Yoji Kanda’s stories, you will find that you can sit back and enjoy them and moreover you will probably understand that they are something from which you can learn; even if your Japanese skills are still growing, koudan still provides important insight into the pan-cultural context of its performance.

This is pretty obvious if you take a look at just a few examples of the topics he covers: ‘Koudan: Bill Gates’, ‘Koudan: Giant Robot’, ‘Koudan: Internet’, ‘Chaplin’, ‘Kurosawa: Life’, ‘Edison: The Man Who Invented the 20th Century’, ‘Koushaku: Palestine’, ‘Scene of Carnage: Hanshin Tigers’, ‘Koudan: Mizuho Bank’, ‘The Merchant of Venice: Revised’, etc. The topics cover a broad range of areas from western literature to Japanese animation, and from sports to economics. Kanda is cutting edge: as soon as the Hayabusa space probe became news he told a story about it, and in place of a book he uses an iPad. He is changing the image of storytelling as a traditional art form from the ground up. With that in mind, we started by asking Yoji Kanda, about what koudan is. Kanda tells us:

‘Generally speaking, it’s story telling. It’s a one-man-show but it has rhythm, and there are parts where it sounds like singing, and because it is melodious there are also parts where it’s like reading a poem. It’s generally thought that the origin of koudan was readings of the Taiheki [Japanese historical epics]. Literature started over 500 years ago and it’s said that reading literature aloud was the beginning of koudan. From educational topics such as Shinto teachings to public entertainment, with the telling of nursery rhymes koudan has experienced many changes making it hard to actually define what koudan is. It was established as a performing art in the Edo period, but really only took off at the end of the Edo period. In the Meiji period, a lot of koushakuba – which were small specialty venues for storytelling – opened and koudan flourished. Then due to the Great Kanto Earthquake many of the scores of venues were destroyed.

‘Then, the increasing popularity of the radio dealt the final blow to koudan. Koudan topics were full of variety. Koudan in the Edo period often focussed on stories about the Tokugawa and war. During the war, it was also used to get men revved up to fight and there were times when it got really rowdy, but after the war it was suppressed. After all, there were many vengeful aspects to it so it was no longer in fitting with the times’.

Kanda, who graduated from the Department of Philosophy, at the School of Arts, Letters and Sciences at Waseda University, is a professional storyteller with a unique history. While for this article Kanda is being interviewed as a performer, when he worked for the entertainment magazine City Road he was the one doing the interviews for performing arts stories. It makes one wonder about his crossover into performing. He first started out getting really into theatre when he was at university, studying it formerly with the Gekidan Seinenza theatre company’s research group. Instead of continuing down the theatrical path, he became an editor, but it was through interviewing his old theatre friends from his university days that he started to have the growing feeling that he belonged on the stage. As a result, he decided to become a professional storyteller. Kanda talks about why telling stories and not ‘performing’:

‘Putting a play on involves a large number of people, so something that happens today won’t make it to the stage the next day. But with storytelling it can. I have always liked drama, I can do it by myself and moreover I thought that storytelling is journalistic.’

Storytelling was the perfect melding of his journalistic experiences as a magazine editor and his desire to perform on the stage. In 1990 he became a disciple of Sanyo Kanda II, and was a minor performer for five years. Then after being second billing for eight years he was promoted to the star performer in 2003. Kanda originally had a strong desire to write original works, however during his time as a minor performer he didn’t write anything. The first thing that he wrote was about the Great Hanshin Earthquake. His hometown of Amagasaki was damaged in the earthquake, and this work was about his own experiences of the disaster; it could be said that the starting point of Yoji Kanda’s work is journalism. Of course, he performs literary works but he gives them his own contemporary perspective. Says Kanda:

‘I have done various things from the stock market to the theory of relativity and haven’t been stuck to a genre or style. Basically, I want to do koudan about things that have moved me and made me cry. Whether I do Shiba Sen [a Chinese historian] or speak about the Edo period, because the people that are listening to me are living in modern times, I always think of a modern pretext for stories from the past. I have also used the iPad. It’s the first time in the world that an iPad has been used in storytelling. These days koudan is about memorisation and there is a tendency to say we shouldn’t use books. But if you have a book then you can bring something to the stage straight away. So I want to revive performances using books. For example I did the piece ‘After the Hayabusa Space Probe’ soon after the Hayabusa came back to earth. I had an iPad on the stage with me instead of a book and showed the audience a NASA movie of the Hayabusa coming back to earth. In the future, I want to try different things by storytelling with an iPad.’

A lot of koudan stories are about news and the latest technology. However, when introducing Yojii Kanda one shouldn’t fail to mention the closing days of the Edo period and the driving force behind Japan’s modernisation the bold innovator, Ryoma Sakamoto – who even now – is immensely popular as a national hero. Kanda comments on Sakamoto:

‘I arrived at Ryoma Sakamoto after becoming a professional storyteller. This is because through playing Ryoma I felt like I could paint a picture of the present day. For example, there are things that we can understand about the situation of globalism that currently surrounds Japan, or the problems associated with the opening of the financial markets, from Perry coming to Japan in the Edo period. Therefore by talking about the popular character of Ryoma Sakamoto, I can talk about the present day. I can even give the pretext of the Iraq War to talk bout the Ryoma and the Sacho Alliance. Why Ryoma Sakamoto has become such a popular person for Japanese people is not because he followed his ideas after a lot of thinking, but rather, he did the right thing wanting to get through to his listeners; he did what he liked doing and as a result he was able to change the world. He is a rare example of where following one’s own free way of living corresponds to changing the world. My feeling of Ryoma is that rather than being an idealist, because he wanted to do business, he saw war as getting in the way so tried to prevent this from happening. The more critical situations increase – such as how Japan and China will deal with each other – so too does the number of people studying about the end of the Edo period and Ryoma increase. This means that in the future I want to write more stories about Ryoma.’

Kanda usually chooses ‘hot’ topics such as the Palestinian situation and financial crimes in contemporary Japanese society. In this, Kanda’s powerful ideas are expressed through his ‘power of words’. Kanda explains,

‘I think words are the most powerful medium. Whether it’s the space probe or the theory of relativity I think it’s better to convey something with words rather than explain it using something like computer graphics. Words are an intense medium. Therefore, I think that they were transformed into a dangerous medium during the war when they were used to rev up the soldiers. Even when it comes to the speeches of politicians, the convincing speeches are those that are like a story. Hasn’t it always been that people who have a way with words have changed the world? Kakuei Tanaka and President Obama are true of this. Former Prime Minister Koizumi also gave speeches that were like a story. Why he was able to convince people is because he went to performances such as kabuki, opera and musical performances and he was able to effectively use his breathing to control the volume of his voice. The volume of movies and television is uniform and set. The rhythm changes in koudan. But just as they seem to have the power to convince, because the rhythm is uniform the audience soon loses interest. Giving a rhythm to koudan was a way of keeping the listeners interest. The worst speeches at weddings are when as with all things the president or whoever is longwinded. Although people at the top may be eloquent they are not good at talking. They have gotten used to receiving praise and a good reaction from the audience. Koizumi was good because he had a cultural interest of listening to other people talk at performances such as theatre. For someone to get good at telling stories it is important to listen to other people’s stories and think about whether people are trying to listen to you. Speak while observing your audiences reaction. Recently everyone’s just becoming a monologue.’

It’s about listening to others talk and trying to get people to listen to you. That is the foundation of communication, however, perhaps that these days there are fewer people who can do this.

If words go one way, they aren’t received by anyone and won’t come back to the person who delivered them. In times like this koudan, which has refined the ‘skill of communication’ fostered in Japan, can teach us a lot from the rhythm of talking to the speed, and the posture of trying to convey something. What Kanda is trying to convey through koudan is truly distinct. Kanda says:

‘I want to appeal to human potential through koudan. When I talk about heroes like Ryoma, my real theme is not nihilism but “what humans can do”. It is creating a picture that “people can do amazing things”. I want to communicate that we can change the world through will and words.’

Kanda says that in the future he wants to do a performance called the ‘Rescue from the Collapsed Chilean Mines and Dostoyevsky’. Regardless of whether it will be a classic, or Russian literature or news from contemporary society, he wants to convey his strong idea about what it means to be a ‘passionate human’. In order to do this, he uses the Internet to talk about many of his koudan. This is because Kanda believes that it doesn’t end at reading something, rather the feeling of seeing something live, with communication through real words, is a powerful experience for people.

Youji Kanda Official Site: www.t3.rim.or.jp/~yoogy

Japan Koudan Association Public Performance ‘Koudan Shinjuku Pavilion’, Youji Kanda ‘Sakamoto Ryouma and the Sachou Alliance’ and others

Date: Wed Nov 10

Location: Shinjuku Nagatani

Address: 2-45-5 Kabukicho, Shinjuku, Tokyo

Telephone: (03)3833 1789 (Nagatani Commercial Affairs)

Waseda Koudan and Rakugo Association Kanda Youji: ‘Ookuma Shigenobu’

Waseda Koudan Rakugo-kai Yoji Kanda ‘Shigenobu Ookuma’

Date: Wed Dec 1

Location: Nihombashi Town Hall

Address: 31-1 Nihonbashikakigaracho, Chuo, Tokyo

Telephone: (03)3383 0962

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment