Only in India

Time Out Delhi takes you behind the curtain of the Indian film industry

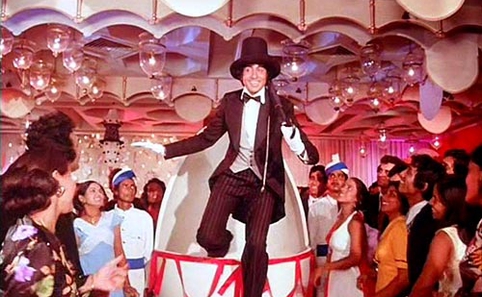

Scene from ‘Enthiran’. @ 2010 SUN PICTURES, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Posted: Mon Jun 10 2013

In 1998, Nikkatsu, one of the oldest film studios in Japan, released Muthu, Odoru Maharaja. It was a dubbed version of the Tamil film Muthu, starring popular actor Rajinikanth. This blithe entertainer was a huge success, running for 23 weeks at Shibuya's Cinema Rise, and eventually reaching some 500,000 Japanese viewers.

Muthu was likely the first Indian film that many Japanese people had seen. It was, in a sense, a representative product – built around a superstar, featuring dance numbers, fight scenes and comic interludes. The industry which produced it makes over 1,000 films every year, in over 20 languages. Its net worth is Rs 93 million and climbing. It’s the largest film industry in the world in terms of ticket sales and quantity of movies produced. Not all of them are good, or original, or even watchable – yet the public keeps coming back for more.

From ten-rupee screenings in tin sheds to 1,200-rupee multiplex shows, cinema is one of the great Indian obsessions, cutting across class, creed, gender and politics. People outside India use ‘Bollywood’ as the blanket term for popular cinema in the country. Yet Bollywood only barely covers the Hindi film industry, and ignores the many, many films made in languages like Tamil (Kollywood), Telugu (Tollywood), Bengali (also Tollywood) and Kannada (Sandalwood).

Masala films

The Hindi word ‘masala’ is a generic term for spices used in cooking. It’s also an adjective – food that’s flavoursome is called ‘masaledar.’ The term ‘masala film’ refers to the several distinct – seemingly contradictory – flavours that a typical Indian film might include. Not for Bollywood directors the restrictive silos of ‘action’, ‘comedy’ or ‘drama’: a masala flick has all of these, often in quick succession, and sometimes all at once.

The director who best embodied the concept of masala was Mahmohan Desai, whose films with Amitabh Bachchan in the 1970s remain some of the most popular in Hindi cinema. His best was 1977’s Amar Akbar Anthony, a riotous comic drama about three brothers separated at birth and raised by Hindu, Muslim and Christian families. This metaphor for religious harmony is typical of Indian cinema – larger messages smuggled in under the guise of family entertainment.

Of course, nothing sets Indian cinema apart as much as its continued loyalty to the musical genre. A key difference between musicals here and in the West is that Indian films don’t need a pretext to break into song. Musical numbers are integrated into the story only in the loosest sense, much like the out-of-the-blue climactic dance sequence from Takeshi Kitano’s Zatoichi. It’s this aspect that makes our films such a puzzle for audiences and critics abroad. But then, every film is essentially a break from reality, and just because films here take slightly longer breaks doesn’t mean the issues they’re addressing aren’t ‘real’ or important.

Not all fun and games

One of the great misconceptions about Indian films is that they’re only concerned with singing and dancing. While it’s true that a lot of them are escapist in nature, there’s also been a persistent realist strain running through Indian cinema, from the now-forgotten 1946 Cannes Grand Prix-winner Neecha Nagar, to films by arthouse faves like Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, through to the parallel cinema of the ’70s and ’80s. The government, which usually steers clear of funding cinema, began providing limited support to envelope-pushing directors through the National Film Development Corporation, established in 1975. Recently, some studios have also begun to back young, innovative filmmakers. Of course, formula still rules – you can see it in the massive success of brainless action comedies in the past few years – but the gradual increase in Indian films making their way to international festivals can only be a healthy sign.

Japanese cinema in India

While Japanese films haven’t found their way into Indian multiplexes yet, there’s plenty of interest in that country’s cinema. For example, in my hometown of Delhi, Japanese animation has become increasingly popular. The Delhi Anime Festival is now in its fourth year, and there are local otaku meets and anime clubs. Japanese feature films are also screened regularly at film festivals and cine clubs, or by the Japan Foundation. Yoshimasa Ishibashi’s Milocrorze: A Love Story won a special award at the 12th Osian’s Cinefan Festival last year, and the same festival also featured a Koji Wakamatsu retrospective.

You may think that theatres in Japan don’t show Indian films either, but another Rajinikanth flick, Enthiran (Robot), was released on 1,300 Japanese screens in 2012, 14 years after the initial success of Muthu. Two years earlier, Chigusa Takaku became one of the first Japanese actors to star in an Indian film, featuring in Aparna Sen’s The Japanese Wife. With Indian cinema attracting more and more global viewers – and, since the introduction of 100 percent foreign direct investment, money – one hopes to see many more such exchanges between the cinemas of Japan and India in the future.

Read more at Time Out Delhi

Tags:

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment