Gotta Have Faith

Shinto and Buddhism are both big in Japan

Posted: Tue Sep 17 2013

Japanese adherents of Shinto number around 106 million, while those regarding themselves as Buddhists amount to 95 million. This tally of around 200 million is not bad for a country with a population of less than 130 million. Clearly, when it comes to religion, the Japanese believe there’s no harm in hedging one’s bets. It’s common for people to have their rites-of-passage ceremonies in a Shinto shrine, their marriage in a Christian chapel and their funeral in a Buddhist temple.

Though the majority of Japanese people happily embrace both native Shinto and imported Buddhism, these are about as different as two faiths could be. For example, Shinto is unconcerned with matters of afterlife, which is a major concern in Buddhism. Shinto is an old faith: it imparts no ethical doctrine and possesses no scriptures. It is at heart a system of animistic belief in natural spirits (kami) – the religious system of an ancient nation of rice farmers that has survived into the modern age. Some of the Shinto religion’s most visible features are its numerous festivals, many of which double up as fertility rites, supplicating the deities to bestow a bountiful rice crop on the community.

Purity has long been a major feature of Shinto, and this is evident at the place of worship (conventionally termed ‘shrine’ in English, to distinguish it from Buddhist temples). After passing through the shrine’s distinctive torii (gate), worshippers often ritually wash their hands and mouth with water from a stone basin before offering their prayers at the main hall.

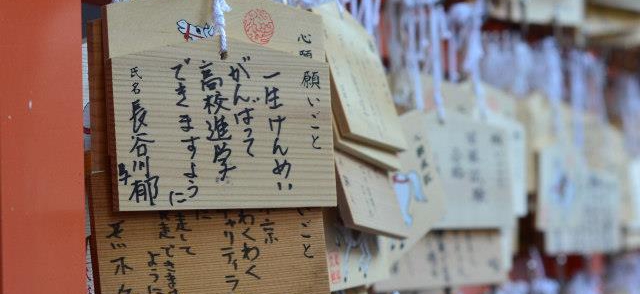

Talismans play an important role, too, so stalls at the shrine sell amulets for luck in health, love, exams and even driving. You’ll also see collections of small wooden plaques (ema) on which people write wishes, white fortune-telling slips of paper (omikuji) tied around trees in the grounds, and sometimes colourful strings of 1,000 origami cranes (senbazuru).

By the time Buddhism arrived in Japan from Korea in the sixth century AD, it was already 1,000 years old, and in its long journey across Asia from India had picked up rituals, symbols and tenets that would have seemed utterly alien to its original founders. Mahayana Buddhism, as practised in Japan, introduced the notion of bodhisattvas, who put off their own salvation in order to bring enlightenment to others. Kannon is a popular bodhisattva, as is Jizo, who is often seen by roadsides and in temples as a small stone figure wearing a red bib.

Temples are often ornate and brightly coloured, while shrines tend to be more muted. At both, people make offerings, often with a ¥5 coin, which is considered lucky. Temples also sell good-luck charms, and commonly feature incense burners; you’ll see people directing the smoke, which is deemed to have beneficial powers, over themselves.

You can’t enter the main buildings at temples or shrines, but otherwise there are no off-limit areas, and locals won’t be offended by sightseers. Photography is widely permitted, though it may be forbidden indoors at some temples – look for signs. You may be required to take off your shoes before entering some buildings.

Must-see religious sites in Tokyo are Meiji Shrine and the Asakusa Kannon (Senso-ji) Temple; if you’re really keen, head to the temple towns of Kamakura or Nikko.

Tags:

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment