Amir Naderi: the interview

‘You cannot make a joke about Japanese culture’

Posted: Sat Dec 17 2011

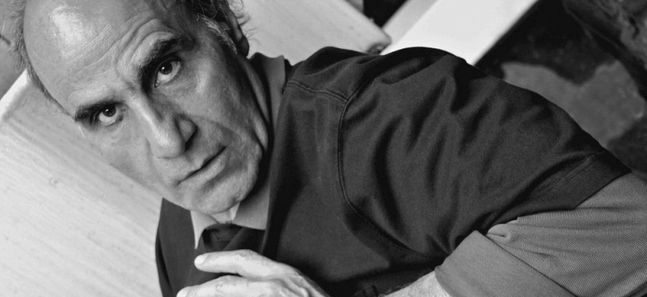

Amir Naderi is getting worked up. When you talk about film with the Iranian director – and he tends to talk about little else – it happens a lot.

‘What is this, today’s cinema?’ he asks, lamenting the caliber of movie on offer at the average multiplex. ‘What the fuck is this? Somebody tell me. All my life, I spent time for cinema because I loved it and because I believed that as art. What the hell is going on?’

It’s a refrain that runs through Naderi’s latest film, which opens in Tokyo this weekend. Cut is part polemic, part tribute to the redeeming power of great cinema – and it’s shot entirely in Japanese. Hidetoshi Nishijima (Dolls) plays Shuji, an out-of-work director and cinephile who finds himself indebted to the yakuza after his brother’s death. Rather than resort to moneylenders, he decides to raise the necessary funds by letting the mobsters pay for a chance to beat him up, all the while railing against the ‘rubbish movies’ that have become the norm in contemporary cinema.

A bold and angry work, the film gives Naderi a chance to vent his frustrations and pay homage to the masters of Japanese cinema at the same time. The action is interspersed with scenes of Shuji visiting the graves of Akira Kurosawa, Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi – filmmakers whose techniques are also incorporated into the movie.

It’s this cinematic legacy that Naderi fears is at risk of being forgotten: ‘Ten years from now, nobody knows who Mizoguchi [is], if you talk to young kids. I worry about it: [there are] so many classic films in this country – Naruse movies, Ichikawa movies, Hamasaki movies, Kobayashi movies, or Kurosawa-san, or Ozu-san, or this and that – but nobody remembers it. “What? Who?” Because cinemas today get fucked up.’

At the climax of Cut, Shuji subjects himself to 100 punches while the names of his 100 favourite films flash up on the screen, from Frederick Wiseman’s Welfare to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. Stretching out for 15 minutes, the sequence is as grueling as it is shamelessly geeky (local audiences might be proud to note that 15 of the films are by Japanese directors). Naderi says he would’ve liked to include 300 movies in the list, but admits that his protagonist might not have been able to sustain the punishment.

So is he saying that he’d die for cinema? ‘Yeah,’ he says. ‘It's there [in the film], no? I cannot ignore it. Between me and you, I don’t have anything in my life besides the love of cinema.’

Naderi has come a long way, geographically if not necessarily commercially, since he won the Palme d’Or for his 1985 film The Runner, confirming his status as one of the leading lights of the New Iranian Cinema generation. He left his native country the same year – citing ‘ambition’ rather than political reasons – and moved to New York, where he has continued to direct while also teaching university film classes.

‘I learned how I can – not change, transition my feeling to another country, another culture,’ he says of his American movies, the most recent of which was 2008’s Vegas: Based on a True Story. ‘Because nobody did it in my country before. Now so many people are coming out of my country and making a movie in another country, but in ’85, nobody: they think I’m crazy.’

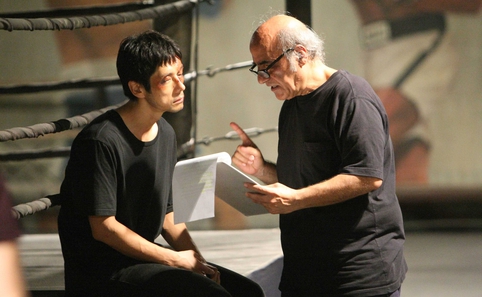

Amir Naderi with Hidetoshi Nishijima on the set of Cut

The initial inspiration for Cut came from Naderi’s relationship with the late John Cassavetes, the forefather of American indie cinema, whose career was a constant struggle with an uncaring movie industry. Naderi worked on the director’s final film, and remembers him as being ‘very disappointed, very ready to die.’ After toying with the idea of making a Cassavetes biopic, he changed his mind when he met Nishijima at Tokyo Filmex festival in 2002 and decided to adapt the story to Japan, recasting the cineaste as a ‘last samurai’ figure. ‘He wants to save something, so he sacrifices himself,’ Naderi says. ‘That reason is very Japanese.’

Though he originally wrote the script in English with Vegas screenwriter Abou Farman, Naderi says he found that too much detail was being lost when it was translated into Japanese – a problem that, surprisingly, was less apparent when translating from Farsi. Enlisting long-term Japan resident Shohreh Golparian, who would work as his interpreter and assistant throughout the shoot, he rewrote the screenplay in his native tongue and had it translated again. The dialogue was later tweaked with help from Nishijima and indie director Shinji Aoyama (Eureka).

His aim, he says, was to do something that visiting filmmakers from Joshua Logan to Sofia Coppola and Quentin Tarantino have failed to achieve: make an authentically Japanese film. ‘Always, I’m very angry to see the films they make about Japan,’ he says (Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour, of course, is the exception). ‘In Hollywood, in the past, like Sayonara and this kind of shit, or the other one – what's the name? – they released it in the past couple of years. I watched it, and that's bullshit: that's not Japanese culture… All of them, if they’re good movies, it’s not about this country. They used the location, that’s it.’

So how did he find working with a Japanese cast and crew? ‘Language is not an issue in this country,’ he insists; ‘you can get an assistant, a translator. The problem is, they don’t want to talk too much. In New York, you sit down at a table, a round table, and talk about the characters… Here, if you give them the script, the script for them is like a bible. [If] they say yes, they say yes about everything, A to Z.’

Naderi’s working methods also provided an occasional source of tension on set, not least his preference for using three cameras that would be positioned before a scene was blocked, then shooting in long, continuous takes. With the exception of a lengthy tracking shot at the start of the film, it isn’t immediately clear why such a technique was necessary, but he insists that it helps keep his actors focused.

‘First I try to explain to them: I know it,’ he says. ‘They cannot do shit with me, never. I know what I'm doing, I know where I came from, I show the film with them, I talk with them, this and that. I never give up even one second, I never compromise… because one day I know it: if the film is finished and it isn’t good then nobody will care about it, and they’ll kill me. I know that.’

Thankfully, the early responses to Cut haven’t been nearly so merciless: the film earned some strong reviews when it played at Venice and Toronto film festivals, and tickets for a gala screening at last month’s Filmex (where Naderi also chaired the jury) sold out in three minutes. However, he seems most enthused by director Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s comment that it was hard to believe the movie had been made by a foreign filmmaker.

‘I’m so proud of these words, because I respect Kurosawa-san,’ he says. ‘He’s a great director, he’s a very serious man. So many other people [have said] that so far in Japan. “This is a truly Japanese movie” – I love that. You cannot make a joke about Japanese culture.’

Vindicated, he’s now setting his sights on an even more ambitious work: a long-mooted movie about the moon. ‘The moon is a very old project, more than 15 years,’ he says. ‘I met Kubrick for it, I told him what I want to do.’

And what did the visionary maker of 2001: A Space Odyssey say? ‘He encouraged me to do it. Of course. Because that one, I want to be very original: to feel that you’re in the moon. That’s it. Experience it.’

Cut is now screening at Cinem@rt Shinjuku. An English subtitled version will go on show at Cinem@rt Roppongi from January 7

Tweets

- About Us |

- Work for Time Out |

- Send us info |

- Advertising |

- Mobile edition |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Privacy policy |

- Contact Us

Copyright © 2014 Time Out Tokyo

Add your comment